I’ve recently discovered Candlestick Press, a small publisher of poetry in Nottingham, and I am so happy to have done so. The highlight of their publications is their collection of ‘cards’ for children that they make. These contain a selection of poetry to give in lieu of a traditional greetings card. After browsing in my local Waterstones, I finally picked one out to have a read.

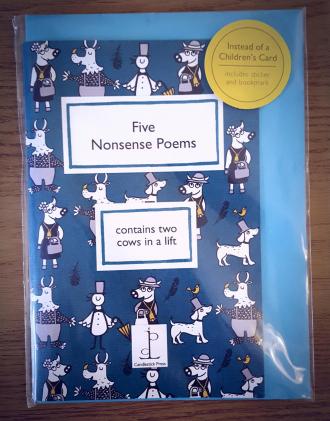

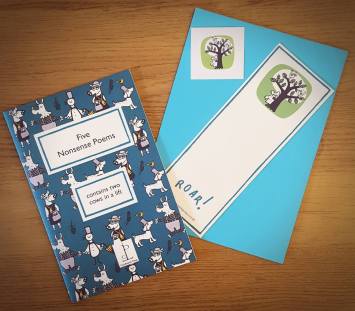

Out of the entire selection on the rotating rack, it’s Five Nonsense Poems that caught my eye. The striking blue of the cover along with the fun illustrations appealed to me, and with my young nephew’s upcoming birthday on my mind I just couldn’t resist.

The paper quality is fantastic. It feels great in my hands; a top quality feel of thick, textured card that tells you it’s been printed and produced by someone who cares. Inside, the pages are just thick enough so that you can’t see through them to the print on the back, with meticulous printing of the ink on each page. There’s not one mistake to be seen; the sign of a talented editor who knows exactly what they’re doing.

I feel that I cannot comment on the actual writing within the pages, as the poems are all selected from previous works, but whoever selected them chose them well. You can’t have a selection of nonsense poems without featuring Spike Milligan, and Carol Ann Duffy’s poem is a great choice for the opening. It was a slight surprise though; I was expecting new poetry from new poets, but what is there does not disappoint. And, if I had bothered to read the blurb rather than being focussed on the cover design, I would have seen the names of all the poets in there and known.

The highlight by far though is the beautiful illustrations by Ruth Green. They’re bold and bright and just what a book of nonsense poems needs. I especially love the illustration that goes with Pauline Clarke’s poem – it’s fun and neat and looks great alongside the poem. Green’s imagination and creativity is what attracted me to the collection in the first place, and her art is the perfect fit for the poems. And, as a collection advertised as being perfect for children, it’s beautiful enough even for the youngest of readers to enjoy.

As a present, it really is wonderful. It comes with a striking blue envelope as well as a high quality bookmark and sticker with illustrations from the collection on them. They’re a nice little touch that gives something extra to the collection. There’s even nice touches on the inside to, like a ‘to’ and ‘from’ page and a page at the back for the receiver to write their own poem or draw their own creature.

I really do love this collection of poetry. It makes a perfect gift for a child or an adult, and has a great quality to it that lets you know the publisher cares. The other collections look equally appealing; in fact, I might go buy the collection of cat poems now.